“For us, as a minority in Germany and in Europe, this project is of historic importance,” said Romani Rose, head of the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma and member of the new archive’s board of advisers, at the presentation of RomArchive, the digital archive for the arts of Roma, launched on Thursday.

For the first time in their 600-year history, Roma have a chance to present their arts and cultures themselves, completely independent of centuries-old prejudices, added Rose.

Counter-history told by Roma

The RomArchive data bank has a collection of 5,000 objects, including photos, texts, videos and sound recordings that show the enormous wealth of Sinti and Roma artistic productions. It quickly becomes clear that there is no such thing as “monochrome” Sinti and Roma art, and that the cultures that often evolved in a close interchange with the majority societies are not only an important contribution to European art history, but that they’ve also not been honored enough.

RomArchive, which is available in German, English and Romani, is set to change that. With its support of €3.75 million ($4.26 million), the German Federal Cultural Foundation is RomArchive’s biggest sponsor.

The archives are a counter-history told by Roma themselves, according to project heads Isabel Raabe and Franziska Sauerbrey. Works of art collected for the project include dance, theater, film, music, literature and Flamenco, categories in which Sinti and Roma present their own cultural history to the present day.

Roma contributed to flamenco music— through “Flamenco Gitano” — a fact that even many Spaniards aren’t aware of, Gonzalo Montano Pena told DW. The musicologist and researcher at Seville University, who curated the archive’s flamenco section, pointed out that a “group of melodies” were actually penned by musicians with a Romani background, for instance David Pena Dorantes, who plays contemporary flamenco on the piano. Dorantes is one of the artists performing at the “Performing RomArchive” opening festival at Berlin’s Academy of the Arts held from January 24 – 27.

n the film section, curator Katalin Barsony chose 35 films that either focus on or were produced by Roma and Sinti from a total of 350, disregarding the movies she felt propagate nothing but stereotypes about Roma life and culture. The archive thus does not include Emir Kusturica’s successful 1988 film Time of the Gypsies, but it includes Lawen Mohtadi’s Taikon, a film about a civil rights activist of the same name. The latter may still be relatively well-known, while the other films are not.

Curators in the dance, theater, literature and music sections followed similarly stringent ethical standards, so most selections will be unfamiliar to the general public.

Against ignorance and racism

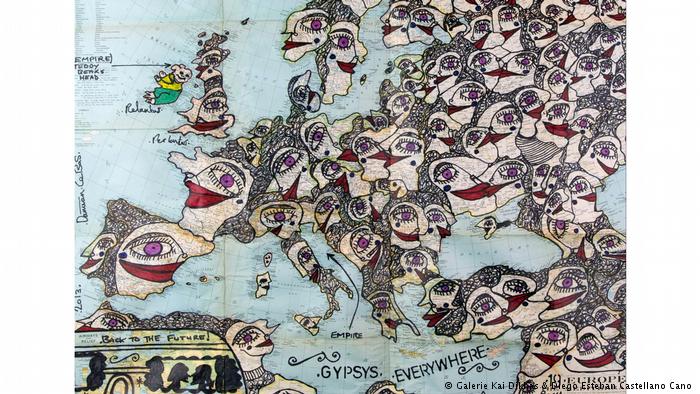

Sinti and Roma mainly blame this on the ignorance and latent racism in Europe’s majority societies and their cultural institutions. Mechanisms of discrimination differ across Europe — they are more subtle in Britain and Germany, and more open in Hungary, Delaine Le Bas told DW. The British-born photographer, filmmaker and performance artist is one of the six artists who in 2007 participated in “Paradise Lost,” the first Roma pavilion at the Venice Biennale. She is also represented in RomArchive.

Few people on the culture scene support Sinti and Roma as strongly as Berlin Gorki Theater director Shermin Langhoff, who in 2018 organized the very first Roma Biennale. “It is still a struggle for Roma artists and for people with a Romani background in general to be granted their rights in European societies,” she told DW, urging change in cultural institutions in a way that would give Roma responsibility in cultural institutions, too, “not only as artists, but as donors, organizers and creative people.”

Steinmeier calls for more appreciation of the Sinti and Roma

There is no doubt that centuries of history marked by discrimination and persecution overshadow the RomArchive. That is evident in the “Civil Rights Movement of the Sinti and Roma” section, which among other things documents the fight against discrimination, known as Antiziganism, and the campaign for women’s rights as well as campaigns against school segregation in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia. Victims of the Nazi genocide tell their stories in the “Voices of the victims” section.

At a culture evening with Sinti and Roma at Bellevue Palace, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier spoke of the “forgotten Holocaust,” adding that people’s awareness of the murder of half a million Sinti and Roma in Europe must be raised. The “often consciously or unconsciously overlooked, neglected, displaced and even suppressed culture” must be appreciated with more care, Steinmeier said.

RomArchive could be an important part of the process. And as far as Romani Rose is concerned, it is not a minute too soon in view of the rise of right-wing nationalist forces in Europe. People more openly reject Sinti and Roma again, he said.

A November 2018 study by the University of Leipzig found that 60 percent of Germans agreed with the statement that Sinti and Roma had a tendency to commit crimes. To get rid of preconceived notions and find out how Sinti and Roma actually contributed to European culture, the RomArchive is the best place to start.